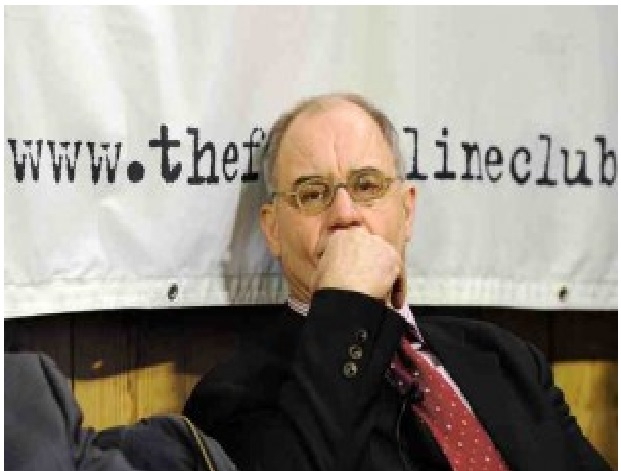

In this post, Sol Picciotto, Emeritus Professor of Lancaster University, provides an update on developments pertaining to the case of Rudolf Elmer which he wrote about in a chapter from the recently published The New Legal Realism Volume II: Studying Law Globally. [above photo: Rudof Elmer at the Press Conference of Wikileaks in the Frontline Club, January 2011.]

My chapter on “The Deconstruction of Offshore”, in the book The New Legal Realism 2: Studying Law Globally used the personal story of Rudolf Elmer to open up some of the fascinating story of the construction and more recent deconstruction of the offshore system.

Elmer is one of several whistle-blowers whose revelations have helped to spotlight some of the otherwise arcane practices of avoidance of tax and other state regulatory requirements developed mainly by lawyers, which helped to shape 20th century transnational corporate capitalism.

My chapter began by noting that of 28 encounters with the Swiss courts, Elmer had lost 27 of them. However, the final decision of the High Court of Zurich dated 19 August 2016 was forced to substantially exonerate him. The court conceded that Elmer was not guilty of breaking the strict Swiss bank secrecy law, since he was actually employed by an entity formed in the Cayman Islands. There is an obvious rich irony here, since this was a subsidiary of the Julius Baer Bank, formed to help its clients avoid tax and other laws, yet the Baer Bank was the main complainant in the case against him. Furthermore, a strongly worded report in the Sonntagszeitung of 30 July 2016 castigated the conduct of the case by the prosecutors, who had failed to disclose documents proving Elmer’s employment status.

In fact, the Baer Bank has had a bad year. As Forbes reported back in February, two of its bankers pleaded guilty, and the Bank itself admitted that it knowingly assisted U.S. taxpayer-clients in evading taxes, agreeing to pay $547 million in a deferred prosecution deal.

The revelations have not been confined to Switzerland, which is just one node of the offshore secrecy system. In April the world was rocked by the publication of the Panama Papers by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. These contained files and emails from the prominent Panamanian lawyers Mossack Fonseca, detailing some of their work for clients around the world. Elmer himself recorded some comments on the implications.

This publicity contributed to the public pressures forcing world leaders to deliver on their promises to end the abuse of this secrecy system. Panama agreed in October to sign up to the OECD’s multilateral convention on assistance in tax matters (although it must still ratify the treaty), and to commit to implement automatic exchange of tax information by 2018. There are still significant gaps: notably the US still stands aside from this multilateral framework, relying on the network of bilateral agreements it has fashioned under the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), even though many of these are not fully reciprocal. Indeed, the US itself remains in many ways an important secrecy jurisdiction for non-US citizens. Research has shown how easy it is to set up a shell company in the US, and state legislatures are resisting pressures to introduce shareholder registration rules. Despite ringing statements that “the era of bank secrecy is over”, although considerable progress has been made, there is still some way to go.