Legal education is a topic of much concern for NLR scholars, as can be seen in the first book of the recent NLR volume set published by Cambridge University Press. During the academic year 2017-2018, we plan to feature blog posts on legal education research. We begin with a guest blog from Professor Alex Steel, who educates those of us outside of Australia on the cutting-edge efforts there, based in part on survey research. As he points out, Australia has been a leader in legal educational reform based on empirical efforts — and as such has much to teach those of us engaged in the legal academy in the U.S. as well as other parts of the world. We hope in the months ahead to share research on legal education from many disciplinary and global perspectives, following the NLR tradition.

Smart Casual: online professional development for adjunct colleagues

In the US the proportion of non-tenure track faculty in higher education generally has been reported to be at 73% in 2014[1] and predicted to rise.[2] These figures include community colleges and so are not necessarily representative of smaller graduate law schools. However numbers of adjunct or adjunct colleagues in law schools are also rising.

The American Bar Association (“ABA”) Standard 403(a) requires that full time faculty:

… teach substantially all of the first one-third of each student’s coursework. The full-time faculty shall also teach during the academic year either (1) more than half of all of the credit hours actually offered by the law school, or (2) two-thirds of the student contact hours generated by student enrolment at the law school.[3]

However this is currently under review by the ABA Standards Review Committee, and if amended adjuncts could be more widely employed. This has been the experience in Australian law schools where no restriction exists.

Estimates put the number of adjunct colleagues in Australian universities at between 40-60% of all teachers.[4] The level of use of adjunct colleagues within law schools may be even higher. Cowley’s 2009 survey of Australian law schools[5] suggested that up to 50% of courses were then taught by adjunct colleagues, a percentage likely to have risen substantially since then. Australia’s 40 law schools[6] range in size, with annual enrolments from 20 to 1000. Even in larger law schools with a strong cohort of permanent research-based colleagues, a decision to teach in small classes/sections can result in very high levels of reliance on adjunct colleagues.[7] One large Australian law school had 75 adjunct academics in 2014, teaching over 50% of the classes.[8]

Despite the importance of the skill of the teacher in assisting student learning,[9] significantly less effort is put into training faculty to teach than is put into training for research. Research training is increasingly seen as fundamental and necessary: indeed the widespread requirement of a PhD as an employment criterion is a proxy for extended research training and demonstrated research ability.[10]

Many universities now include generic teaching workshops for colleagues beginning their academic careers – including adjunct colleagues.[11] Our 2014 survey of Australian law schools indicated that 75% of their adjunct colleagues attended such generic university-wide induction.[12] However, the same survey indicated that there is little formal discipline-specific training for commencing law teachers, with only 25% of schools offering any training beyond administrative orientation.[13] In a US context, Popper described such training as Mirandising – the indoctrination of a series of warnings about student and staff rights.[14] While important, they are only the beginning of how adjunct colleagues learn to teach in that law school’s environment.

Consequently, much training of law teachers occurs ‘on the job’ in local contexts, and approaches vary considerably.[15] There is a widespread assumption that new faculty can expect a supportive mentoring environment with colleagues who will nurture and mentor their teaching; though whether this is adequate, if it indeed happens, is moot.[16]

While such support might be potentially available for permanent colleagues, the same does not apply to adjunct colleagues.[17] Indeed, the lack of institutional support for the professional development of adjunct colleagues is increasingly recognised at a national level.[18]

The Smart Casual: Promoting Excellence in Sessional Teaching in Law project http://smartlawteacher.org (“Smart Casual”) seeks to address this priority by developing online, law specific professional development modules.

Many adjunct colleagues are not invited to law school induction teaching workshops that go significantly beyond administrative matters. In terms of any further support, the Smart Casual survey indicated only 36% of law schools invited adjunct colleagues to professional development sessions.[19] The ABA Best Practices Report found a similar percentage of schools offered professional development programs.[20] Where they are invited, adjunct colleagues may be unable to avail themselves of the opportunities to attend due to their other work commitments and out-of-hours teaching times.[21] This will also mean they are not able to create networks and collegiality as do permanent colleagues. The precariousness or last minute nature of their employment may also militate against their ability to build collegial links or attend development forums (for which they may in any event not be paid to attend or to which they might not be invited).

Adjunct colleagues are also likely to encounter teaching issues from a different perspective to that of permanent faculty. Adjunct colleagues often have far less autonomy in setting curriculum and assessment, and often in the way they teach classes.[22] Consequently, professional development resources for adjunct colleagues must be framed within those limitations.

Further, law confronts specific challenges in responding to the challenge of supporting adjunct colleagues. Discipline-specific skills and content form substantial components of law curricula. In Australia, graduates must meet discipline-developed national Law Threshold Learning Outcomes (TLOs)[23] and professional admission requirements.[24] Both of these go beyond mere mastery of content and include a range of skills such as ethical conduct and communication and collaboration. Similar requirements are now part of the ABA standards for US law schools.[25]

Adjunct law teachers are often time-poor legal practitioners weakly connected to the tertiary sector. While highly skilled, practitioners may be under-prepared for the complexity of legal education’s current emphasis beyond content. Many will have been taught in environments that are significantly different to current pedagogical environments. For example, until the 1980s legal education in Australia was primarily positivist in approach, teaching a narrow range of legal doctrines and processes of reasoning, at times by rote. Since that time, there has been broad recognition of the need to teach law within its broader social context, and to involve students as active participants in the learning process.[26] These needs were primary drivers in developing the TLOs. However there are varying levels of awareness at faculty level of these important innovations. This is particularly true of adjunct colleagues who can come and go without awareness of these trends, and may only be familiar with the approach to teaching that they themselves encountered as students.[27] Further, they are unlikely to have the time for large-scale training, nor see the need for it. This distinctive context demands discipline-specific and targeted training for adjunct colleagues in law.[28]

The national need for professional development opportunities and resources for adjunct law faculty is being addressed by the Smart Casual project. While written with primarily Australian colleagues in mind, much of the content is of relevance internationally.

Surveys of law school Associate Deans Australia-wide and three localised surveys of adjunct colleagues, suggested adjunct colleagues were most interested in gaining assistance with facilitating critical thinking among students; encouraging and managing class participation; providing feedback; facilitating student understanding of substantive content and knowing how to deal with student wellness issues.

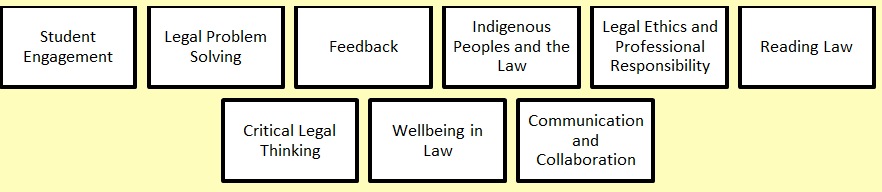

We have now finalised a full set of nine topics based on the surveys and trial participant feedback:

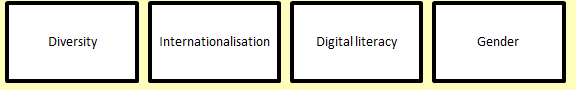

Further, we have sought to identify and weave throughout the modules four strategic themes critical to law and law teaching:

The online modules can be accessed freely by law teaching colleagues worldwide.[29] We expect

the modules to satisfy some, but not all, of the principles of best practice academic development. They are designed to be time efficient and available on an ‘as-needs’ basis, so adjunct colleagues can use them as and when required. However, we recognise that in isolation the resources will not engage adjunct teachers in collaborative endeavour nor in the collegial discussions, which are important in developing teaching expertise. They are, however, an important first step in that direction and provide a set of resources around which individual law schools can build programs.[30]

The modules are designed to be ‘SMART’: ‘Specific’ to the teaching of law; ‘Meaningful’ to the needs of law teachers; ‘Accessible’, allowing adjunct teachers to access and refer back to the resources as required; ‘Realistic’, easily applicable to the varied contexts in which session teachers work and their many roles; and ‘Time-efficient’ by being as concise as possible without sacrificing content. Each module consists of a literature review and resources guide, and a toolbox of strategies and ideas based on sound pedagogical principles that can be accessed by adjunct colleagues to support and improve their teaching practices.

What distinguishes the modules from many other online teaching modules – both those designed for colleagues and students – is the interspersing of short video interviews of adjunct colleagues. This is intended to de-centre the authoritative text of the modules and provide a nascent sense of a community of practice – both discussed below. We were very fortunate to have adjunct colleagues from around Australia generously give their time to be interviewed. The interviews have been captured as short YouTube clips that are linked from the modules.[31]

The writing of the modules has also led to a number of journal publications which provide further elaboration of issues and themes:

“Fostering “Quiet Inclusion”: Interaction and Diversity in the Australian Law Classroom”, Journal of Legal Education 66 (2017) 332

“Critical legal reading: the elements, strategies and dispositions needed to master this essential skill”, 26 (2016) Legal Education Review 187

“Working The Nexus: Teaching Students To Think, Read And Problem-Solve Like A Lawyer”, 26 (2016) Legal Education Review 95-114

“Interaction and diversity in the Australian law classroom”, 39 (2016) Research and Development in Higher Education: The Shape of Higher Education, M. Davis & A. Goody (Eds.), 39 (pp 127-136), Fremantle, Australia, 4 – 7 July 2016

“Beginning to Address ‘The Elephant in the Classroom’: Sessional Law Teachers’ Unmet Professional Development Needs” 38 (2015) University of New South Wales Law Journal 240.

NOTES:

[1] Higher Education at a Crossroads: The Annual Report on the Economic Status of the Profession (2015-2016) American Association of University Professors <https://www.aaup.org/sites/default/files/2015-16EconomicStatusReport.pdf>.

[2] David N Figlio, Morton O Schapiro and Kevin B Soter, ‘Are Tenure Track Professors Better Teachers?’ (Working Paper 19406, National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2013) <.http://www.nber.org/papers/w19406.pdf>.

[3] American Bar Association, 2016-2017 Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of Law Schools (2017) <http://www.americanbar.org/groups/legal_education/resources/standards.html>.

[4] Douglas Davis, Bruce Perrott and Len J. Perry, ‘Insights into the Working Experience of Casual Academics and their Immediate Supervisors’ (2014) 40(1) Australian Bulletin of Labour 46; Percy et al, above n 2.

[5] Jill Cowley, ‘Being Casual About Our Teachers–Understanding More About Sessional Teachers in Law’ [2010] (48) The University of New South Wales Law Research Paper <http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1702630>.

[6] Studying Law in Australia, Australia’s Law Schools (26 April 2016) Council of Australian Law Deans <http://www.cald.asn.au/slia/lawschools.cfm>; While the US has 5 times as many law schools (205 ABA approved in 2016), the US has 13 times the population (318million: 23.6 million in 2014).

[7] Cowley, above n 9.

[8] Rachel Hews, Jennifer M Yule and Justine Van Winden, ‘Sessional Academic Success : The QUT Law School Experience’ (2014) 7(1-2) Journal of Australasian Law Teachers Association 15.

[9] See e.g., Keith Trigwell, Michael Prosser and Fiona Waterhouse, ‘Relations between Teachers’ Approaches to Teaching and Students’ Approaches to Learning’ (1999) 37(1) Higher Education 57; John B Biggs, Teaching for Quality Learning at University: What the Student Does (McGraw-Hill Education, 2011); Paul Ramsden, Learning to Teach in Higher Education (Routledge, 2003). <https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=AsIK_4wAJz4C&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=biggs+teaching+for+quality+education+2nd&ots=XKVIVGGeNp&sig=0fe694Cv9RuFN9ft1AmCuxHSH_4>.

[10] Andrew Norton, J Sonnemann and I Cherastidtham, ‘Taking University Teaching Seriously’ (Report 2013-8, Grattan Institute, July 2013) 15. <http://apo.org.au/files/Resource/grattaninstitute_takinguniversityteachingseriously_july2013.pdf>

[11] John Burgess et al., Managing temporary workers in higher education: still at the margin?, 35 Personnel Review 207–224 (2006).

[12] Mary Heath et al, ‘Beginning to Address “The Elephant in the Classroom: Sessional Law Teachers” Unmet Professional Development Needs’ (2015) 38(1) University of New South Wales Law Journal 240, 240, 249.

[13] Id. at 250.

[14] Andrew F. Popper, The uneasy integration of adjunct teachers into American legal education, 47 Journal of Legal Education 83–91, 84 (1997).

[15] Heath et al, above n 16; For online discussion of these issues from non-law school sessional viewpoints see for example the blogs: A Home Online For Casual, Adjunct, Sessional Staff and their Allies in Australian Higher Education (2016) CASA <https://actualcasuals.wordpress.com/>; Casual Voices (2016) Uni Casual <http://www.unicasual.org.au/casual_voices>.

[16] Cf Andrea S Webb, Tracy J Wong and Harry T Hubball, ‘Professional Development for Adjunct Teaching Faculty in a Research-Intensive University: Engagement in Scholarly Approaches to Teaching and Learning’ (2013) 25(2) International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 231, 232.

[17] Gouvin, supra note 6 at 12.

[18] In the US context see for example, Colleen Flaherty, Non-Tenure-Track Faculty Members Say They Want More Professional Development, With Compensation (27 August 2015) Inside Higher Education <https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/08/27/non-tenure-track-faculty-members-say-they-want-more-professional-development>; In an Australian context see the discussion in Heath et al, above n 19.

[19] Heath et al., supra note 19 at 251.

[20] Gouvin, supra note 6 at 12.

[21] Jill Cowley, ‘Confronting the Reality of Casualisation in Australia: Recognising Difference and Embracing Sessional Staff in Law Schools’ (2010) 10(1) The Queensland University of Technology Law and Justice Journal 27.

[22] For a provocative description of this dilemma see: Working as a Casual? Zip Your Lip and Do as You’re Told (22 April 2016) The Guardian <http://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/2016/apr/22/working-as-a-casual-zip-your-lip-and-do-as-youre-told>.

[23] Sally Kift, Mark Israel and Rachael Field, ‘Learning and Teaching Academic Standards Project, Bachelor of Laws Learning and Teaching Academic Standards Statement’ (Australian Learning & Teaching Council, December 2010); Council of Australian Law Deans, Juris Doctor Threshold Learning Outcomes (2012) Legal Education Associate Deans’ Network <http://www.lawteachnetwork.org/tlo.html>.

[24] See Law Admissions Consultative Committee (LACC), Uniform Admission Rules (2014) Law Council of Australia http://www1.lawcouncil.asn.au/LACC/images/pdfs/Uniform_Admission_Rules_2014_-_June2014.pdf.

[25] American Bar Association, 2016-2017 Standards and Rules of Procedure for Approval of Law Schools: Chapter 3 (2017) <http://www.americanbar.org/groups/legal_education/resources/standards.html>.

[26] Alex Steel, Good Practice Guide (Bachelor of Laws) Law in Broader Contexts (2013) Legal Education Associate Deans’ Network <http://lawteachnetwork.org/resources/gpg-broadercontexts.pdf>.

[27] The reverse is also quite possible – an innovative sessional colleague constrained by uninformed permanent colleagues who control the curriculum.

[28] Heath et al., supra note 19.

[29]Smart Casual, About <https://smartlawteacher.org>; Smart Casual, Background to the Project <http://www.lawteachnetwork.org/smartcasual.html>.

[30] Some initial ideas of how such programs can be developed are discussed in eg Catherine F Brooks, ‘Toward “Hybridised” Faculty Development for the Twenty‐first Century: Blending Online Communities of Practice and Face‐to‐Face Meetings in Instructional and Professional Support Programmes’ (2010) 47(3) Innovations in Education and Teaching International 261; Norman Vaughan and D Randy Garrison, ‘How Blended Learning Can Support a Faculty Development Community of Inquiry’ (2006) 10(4) Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 139.

[31] The external linking is due to technical difficulties we have not as yet overcome with the placement of videos inside the modules.