Here is Professor Clune’s continuation of the exchange between himself and Professor Bucci! This is the 4th part of our ongoing blog that contains and exemplifies efforts to translate between law and public policy – as well as between Global South and Global North. This is an endeavor NLR has encouraged from its beginning: see, e.g., Huneeus & Klug, “Lessons for new Legal Realism from Africa and Latin America,” in Research Handbook on Modern Legal Realism (Edward Elgar 2021); Klug & Merry, “Introduction” to NLR Vol. II Studying Law Globally (Cambridge U.Press 2016); Garth & Mertz, “Introduction: New Legal Realism at Ten Years and Beyond,” UC Irvine Law Review 6(2): 121-135(2016); Merry, “New Legal Realism and the Ethnography of Transnational Law,” 31 Law & Soc. Inq. 975 (2006); Garth, “Taking New Legal Realism to Transnational Issues and Institutions,” 31 Law & Soc. Inq. 939 (2006).

LAW AND PUBLIC POLICY: WHAT IS IT, SKILLS OF PRACTIONERS AND RESEARCHERS, RESEARCH DESIGNS AND METHODS, LAW SCHOOL COURSES

William H. Clune[1]

Professor Maria Paula Dallari Bucci[2] and I have been collaborating on law and public policy (LPP) for about a year.[3] This article is an effort to pull the previous work together, explain LPP in clear terms, discuss the skills and knowledge required for practitioners and researchers, and summarize research designs and methods appropriate for LPP research studies. A previous version was published with SSRN.[4]

What is LPP: the area to be studied

The “public” aspect refers to public goods or lack thereof — where people experience harms or deprivations that cannot be remedied by private transactions or individual legal remedies and therefore require collective action through politics.[5] “Law” refers to rules broadly understood: – legislation, implementations, administrative rules, judicial holdings, tax subsidies, executive orders, official rule interpretations, official influence, and implementation. LPP “policy” is law designed to improve the general welfare, protecting the public from harms and harmful deprivations, including equity for those experiencing especially low levels of welfare. In other words, the goals of LPP are progressive even as LPP research necessarily studies both gains and losses of progressive goals (both counter factual aspirations and factual progress or regress).

The impact of policy is an essential component of LPP that differentiates it from legal interpretation and doctrinal analysis. Legal doctrine and interpretation of laws are part of LPP but only as an aspect of policy aimed at leading to real consequences. “Policy” also refers to existing models with known impacts and which therefore can be adopted and evaluated in new settings. Models for policy represent aggregated social knowledge (i.e., social capital).

Politics is an intrinsic and essential component of LPP. Policies are made by politics. LPP involves the political actions, political parties, and interest groups seeking reform as well as those holding progressive reforms in place or seeking retrenchment. In a sense, policies – and policy implementation – represent never ending fluid alluvial equilibriums in the shifting tides of politics.

LPP importantly includes intentional, organized, planned, and potential efforts to change the rules. These are progressive reform efforts aimed at extending public welfare and equity, planned, in progress, and completed, the social movements and actors supporting such change, and the opposite – reactionary change efforts aimed at eroding progressive laws and institutions – sometimes with disagreements over which policies are and are not in the greatest public good.[6] Perhaps we might distinguish PLPP, progressive LPP, from RLPP, reactionary LPP, because LPP activists from both directions require the same set of knowledge and skills. Yet so many urgent social needs require progressive action. Potential benefits for the public good arise overwhelmingly in a progressive direction (just as protection of existing property rights and wealth stratification are common obstacles). Greater equity is only the most obvious example.

And so, LPP consists of sets of rules affecting the public good, national, regional, and local, sometimes rules from different jurisdictions, agencies, and courts affecting the same policy area, sometimes pushing in contradictory directions lacking policy coherence. On the other hand, the bedrock of LPP consists of stable legal institutions governed by a coherent legislative charter usually involving administrative rules and rulemaking, the “administrative state.”[7] Such institutions typically consist of aspects the welfare state: consumer protection, insurance, securities regulation, health services, education, income support, disaster relief, sanitary systems, worker protection, environmental protection, parks and recreation, transportation infrastructure, bankruptcy relief, affordable housing, etc. Institutions which nevertheless are routinely subject to frequent modifications of law and implementation which bolster or undermine the legislative purpose. One source of fluidity is that the impact of policies provokes reactions by the people and organizations affected — in compliance or non-compliance, lobbying, and the flexible interactive dynamics of policy implementation.[8]

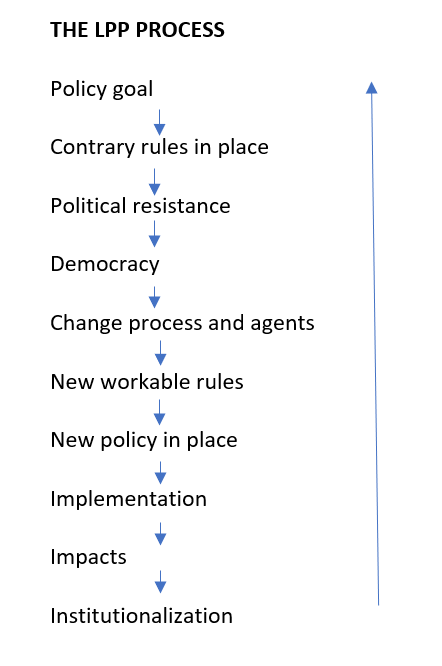

A schematic version of the LPP policy process might look like the graphic below. The reverse upward arrow signifies the iterative nature of the process at each step and over the whole process.[9]

The origins of policies designed to improve general welfare rest ultimately on the interdependence of people who experience the consequences of other people’s actions, negative or positive (as when educated workers benefit the entire economy). In the U.S. public welfare policies are distributed across the national, regional, state, and municipal levels. U.S. states have traditional “police power” entailing potentially every aspect of the general welfare. National policy arises because of national interdependence, interstate commerce, and the fiscal and technical capacity of the national government to deal with national problems, such as disaster relief. One multi-level case is that educational policy and finance in the U.S. is distributed across national, state, and local levels. For example, alignment of standards for curriculum and testing in the United States was organized across states with federal assistance.[10]

How is democracy part of LPP? First, human rights, personal freedom from state coercion, freedom of speech, religion, and assembly, and guarantees of suffrage, should be considered as ends and not only means of progressivism, as reflected in the U.S. Bill of Rights and subsequent amendments and state constitutions. Such rights are essential components of the public good and general welfare.

Second as a means of enactment progressive policies democracy is a system affording political representation of all groups affected by the public welfare, thus allowing advocacy for a broad range of social goods, as opposed to political systems with powerful representative biases, such wealth or geographic region, and especially authoritarian systems where the distribution of goods is decided by autocrats. Professor Bucci and I have considered a typology of welfare states as stable, contested, and illiberal. Stable social democracies like those in western Europe have established institutions of social welfare and labor relations with longstanding democratic institutions embracing the entire community of citizens together with, admittedly, some serious divisions over issues like immigration. Contested welfare states are those like the U.S. and Brazil where major political conflicts exist, in the U.S. especially over redistribution of income. Democracy in the U.S. is threatened by voter suppression and subversion and representative biases like gerrymandering.

The basic reason for autocratic attacks on democracy is that one group of actors – the wealthy, corporations, rural constituencies – wishes to suppress democratic demands from other groups. In other words, autocratic groups and interests do not wish to be held accountable to the needs of large sectors of the population. Illiberal welfare states minimize democratic accountability. Hungary and Russia are examples. Control of the media, courts, and elections are hallmarks together with corruption and cronyism benefitting autocrats and elites. Extreme autocracy is characterized by complete absence of an independent judicial system or free press capable of checking the state, a realistic concept of human rights that might interfere with official policy, or personal freedom free from state surveillance and detention. Illiberal states may have populist or “progressive policies” such as price controls and subsidies for essential goods like food and fuel. China has an extensive array of public welfare policies controlled by the communist party, and is to that extent progressive, but lacks political democracy.

Progressives who are disappointed with the reversals and resistance in democratic societies might consider what is like to have policies determined by autocrats with no means of registering discontent and no accountability. Conservative supporters of free enterprise should dislike state-imposed limits on personal freedom and crony capitalism, even as they seek disenfranchisement of progressive groups. The obvious goal for progressives in contested systems like the U.S. is resistance to voter suppression and pursuit of the goal of universal enfranchisement.

A word about courts as guarantors. The current conservative composition of the U.S. Supreme Court signals a return to the role of courts as opponents of democracy and progressive reform, welfare legislation and the power of administrative agencies. In the long run of history, the Court has been a reactionary rather than progressive institution, with the exception of the Warren Court era from about 1955-1975.[11] Conservative courts can tear down progressive policies and institutions but are powerless to rebuild them.[12] Fortunately, the negative power of the Court usually has been limited to the erosion of progressive reforms around edges, perhaps because of the limited powers of courts in deciding individual cases, bipartisan support for many progressive reforms, or unwillingness to engage in wholesale destruction. To be fair, the Court has been the source of many progressive rights in the past and may be so again in the future. Also on the positive side, state and local courts in the U.S. sometimes can be a source of progressive reform and greater democracy.[13] Strengthening the capacity of cities to deliver public goods should be a top priority for progressives in this time of federal and state retrenchment, and cities have the resources to build powerful public/ private partnerships.[14]

More broadly, while the extent and prospects for policy reform may seem bleak, as with gridlock at the national level over some policies, the silver lining is that progressive reforms are always present, planned, and ongoing at every level of government. Reforms may be bigger or smaller in scope, and they occur in every area of public policy: public education, urban planning, sanitation affordable housing, environment, sanitation, and so forth. To cite a few examples, universal basic income programs,[15] universal childcare programs,[16] a successful homeless program in Houston Texas,[17] policy options for drying of great Salt Lake,[18] and preschool education.[19] In Brazil, Professor Bucci’s students are doing LPP research at various levels of government, see Appendix A.

Expertise required for LPP

Lawyers, social scientists, political actors, policy analysts, and change agents require a distinct core of common knowledge and skills in their respective roles. One piece is sophistication about the dynamics and effects of public policy, including models of good public policy. Also, deep understanding of the multiple rules and agencies involved in specific policy areas such as education, etc. Plus, an understanding of the political forces and actors holding the extant rules in place and those moving toward change. Each academic discipline has insights into aspects of LPP, economics, social sciences, law, etc., and research and change efforts are often interdisciplinary which therefore requires skills of interdisciplinary collaboration. Legal actors should be adept at representing interests for and against the public good. Change agents need skills involved consensus building and compromise (in hearings, negotiations, drafting regulations, etc.)

Looking ahead to the next section, research can make knowledge and expertise more widely available. Reforms can be studied with different research designs and at different depths. Reports and theses can be longer or shorter. There is no end of progressive reforms to study. LPP is a great field for lawyers, policy analysts, and researchers.

LPP research designs and methods

LPP research begins with research questions derived from the general framework of the area to be studied (law, public policy and dynamics). Each policy context must be understood in depth

Researchers should be conversant with existing policies, and new models. Research questions consistent with the approach taken here are:

1) What is the area to be researched, namely LPP? Plans or opportunities to advance the public good through a change in policy or implementation of policy

(a) Policy refers to law, rules, and official practices, that is, collective action

(b) Public good refers to an increase in general welfare including equity

(2) What social and economic benefits are intended and for which social groups?

(3) What kind of politics will be required to make new policy or modify an existing policy including the politics holding the existing policy in place and those supporting change?

(4) What are models for the new policies that are being relied in use elsewhere or specified in theory?

(5) How will technology and financial resources be involved and coordinated in plans for change?

(6) How will efforts to change policy will be organized, including the actors seeking change and those opposing or likely to oppose, and any public/ private partnerships?

(7) What is a good model for evaluation of the intended change process, policy changes, and outcomes, and how can the model be used to track change as it occurs, including shifts and compromises?

Note how law and policies are central. The research questions are law-centric but also involve an interdisciplinary perspective – not just the text of laws but law in action. Existing polices and proposed policies, plans for actors involved in change, resources and technology, and a plan for evaluation. Evaluation can begin with a theory of change, the anticipated activities, implementation, expected outcomes. A basic sketch of the theory of change, often called a logic model, can be helpful in organizing one’s thinking.[20] Logic models are useful for every kind of research discussed in the next section up to and including randomized control trials (RCTs) which must define and control the type of intervention being studied.[21]

Research Methods

Various research methods are appropriate for LPP: case studies, original and secondary data, cross-sectional and longitudinal designs, estimates of effects, costs and benefits, evaluation of change efforts.[22] One common method for doing research on complex policies in specific contexts is the case study. Case studies are holistic qualitative research and “thick descriptions” of a complex situation and its dynamics. We believe that law trained professionals are perfectly capable of doing case studies with a manageable amount of reading, training, and supervision. “This method of study is especially useful for trying to test theoretical models by using them in real world situations. An advantage of the case study research design is that you can focus on specific and interesting cases.”[23]

“Case study method enables a researcher to closely examine the data within a specific context. In most cases, a case study method selects a small geographical area or a very limited number of individuals as the subjects of study. Case studies, in their true essence, explore and investigate contemporary real-life phenomenon through detailed contextual analysis of a limited number of events or conditions, and their relationships. Yin (1984:23) defines the case study research method “as an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context; when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident; and in which multiple sources of evidence are used.” [24]

Case studies are well suited for research on LPP because LPP almost always involves multiple actors with different agendas, complex politics, unique social and economic contexts, and so forth. Research requires delving into complex settings, unpacking, decoding, surfacing and explaining patterns

Research designs and data. If case studies are the research method, the next question is research design, point in time or longitudinal, and the source of data: secondary sources or original research.

LPP case study type #1: “Static” or cross-sectional analysis of legal rules impeding and permitting progressive change. LPP research is always change-oriented, but it is not necessarily longitudinal, that is, a study of change over time. Type #1 is an analysis of the legal rules permitting and impeding change – the rules and political forces holding the rules in place while having some potential for change.

My article on the Political Model of Implementation is an example of cross-sectional analysis with some longitudinal emphasis.[25] Almost any policy area or institution can be studied in this fashion. For example, there is a book on I how the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) operated during the Trump administration (a neglected area of executive discretion).[26] A summary of this research could be written from a LPP perspective, e.g., the rules allowing and permitting change (if the whole book does not already do so – I haven’t read it yet).

LPP case study type #2: research on change in rules over time drawn from secondary sources. My article on the recent history of progressivism in the U.S. was deliberately chosen as a longitudinal study of research on progressivism in the free enterprise active state drawn entirely from secondary sources, that is, with no original collection of data.[27] Here is a quote from the article:

“Because my work was from the 1980s and described policy formation and implementation at a moment in time, I thought it would be helpful if I updated the empirical setting and placed it in a longitudinal context as a test of its hypotheses about the dynamics of the legal process. The longitudinal context, or case study, is the long history of progressivism in the United States including the recent conservative counter movement.”

LPP case study type #3: longitudinal research on progressive change projects. The third type of case study is on-site original research on progressive efforts to change policy over time in a particular location or context. Data collection is oriented to a change in legal system over time.

Such studies could be deep and gather extensive data over a period, as would be typical for graduate theses, or could be a shorter retrospective study based on interviews, for example.

Data for LPP case studies. What about data? Research data for LPP case studies of all types is typical of case studies in general, qualitative research drawn for a wide variety of sources appropriate for the research questions. Typical sources are secondary sources, legal materials, background research on the type of policy to be studied, interviews with policy makers and stakeholders, program publications, documents, archival records, artifacts, observation, journalistic sources, and other opportunistic data. How such data are drawn together and presented in a framework supporting a LPP theoretical perspective is the essence of the research method for a particular study, and it is part science and part skillful and fact-based narration.

Potential law school courses and training in LPP

An interesting question is how law students might be introduced to LPP. An introductory course might include a general survey such as this article, readings of case studies and other research on LPP in various areas, a final paper or thesis based on each student’s research into an LPP problem or intervention, and visits from researchers who have been involved with interdisciplinary collaboration. Researchers steeped in various areas could easily put together units, attending to our framework and suggested research questions. In addition, seminars could be offered in specific areas of LPP such as environment, education, income support, etc., For specialized seminars, joint offerings with other departments, cross listings, and so forth, seem advisable and a way to reach enough interested students and foster interdisciplinary collaboration.

Background like this for law students and lawyers should enable them to understand the legal aspects of LPP in context, perform as advocates and advisors, do research like case studies, and be comfortable as informed members of interdisciplinary teams. Additional technical training would be necessary for technical and quantitative research up to and including degrees in fields like economics, political science, sociology, and history.[28]

Conclusion

A significant challenge for an overview of LPP like this article is dealing with a wide range of public policies each with its own specialized body of research, the equally broad range of research methods, and the many academic disciplines with perspectives on LPP. LPP is multi inter disciplinary at the intersection of many fields of study. From the beginning we intended this work as an analytical introduction, a first chapter in an introductory course, a primer on how to get around in the world of LPP, a map from an altitude high enough to encompass the entire terrain. We aimed to identify the area to be studied, propose a general framework, and identify cross cutting research questions. Once the area of study has been identified — the salient institutions and behaviors — research can be grounded in common understandings, and research in different disciplines can be understood within a common framework.

Small-scale local action projects are simpler to integrate than large topics like the institutions of the welfare state (important as it is). Every local problem occurs in a specific sub-area of policy in a specific context, time, and place. This naturally leads to interdisciplinary problem solving, various kinds of useful research, and a focused search for models of good policy. Site specific interventions can be well studied with the case study method as explained above. In other words, small-scale progressive change efforts are not so hard to comprehend and provide comfortable settings for our suggested common framework. Specific progressive projects are LPP in action (as is LPP of the welfare state on a larger scale).

Appendix A

These are abstracts of research projects by students of Professor Bucci.

Frederico Haddad

Urban Streets Regulation under Law and Public Policy Approach

Urban streets are the main public good in cities. Considering the hegemonic condition of the urban area in the contemporary social organization, they are one of the most strategic state assets, especially when it comes to local governments. Studying urban streets and their social purpose using this methodological approach allowed me to develop several theoretical and empirical arguments. The policy pattern of urban street construction and regulation in the US, Brazil, and many other car-centered countries, was responsible for deepening the existing and creating new forms of inequalities. It also contributed to gradually eliminating many essential functions of streets. As a result, this process emptied streets’ intrinsic free and open uses and exacerbated social exclusion and segregation without delivering an efficient mobility system.

In the first decades of the car-centered model implementation, an entirely legal framework was built to legitimate it and organize its operation. Then, after receiving legal legitimation and cultural hegemony, the model was ready to incrementally self-reproduce. Massive and expensive transformations compatible with the model’s functioning became naturally accepted, while minimal interventions in the opposite way turned into serious offenses to the established order. The capacity to silently replicate and expand its domain showed plenty of strength, creating a clear contrast in most metropoles. On the one hand, the legal city, where the laws prescribe a more democratic, fair, human, and efficient pattern of street use. On the other hand, the actual city, where the car-centered hegemony still reigns, produces inequality and environmental damages.

Having this diagnosis in mind, one of the main contributions of my research was to formulate an original typology of the local government’s decisions concerning the uses of urban streets and apply it as a methodological tool to build legal parameters to assess streets’ social purpose. Decomposing and systematically organizing the public options regarding street regulation are important steps to the necessary demystification and politicization of street planning and management. The typology is useful to fully understand and interpret the legal framework applicable to urban street management according to its social purpose, international guidelines, and scientific evidence historically accumulated. Urban streets are valuable and scarce goods subject to intense dispute between opposed interests.

Gabriela Campos Sales de Azevedo (Federal judge, she coordinated the translation task of The Political Model)

The Institutionalization of Public Policy Systems in Brazil: a Comparison Between Health, Social Assistance, And Education

The ongoing research focuses on institutionalizing a specific model of social or national system model. The emergence of this model is related to two major changes resulting from the Brazilian Constitution of 1988: the adoption of a universalist welfare paradigm and the definition of a cooperative model of shared social responsibilities. Considering these constitutional parameters, the study compares the trajectories by which the Unified Health System and the Unified Social Assistance System were institutionalized and the attempt to establish the National Education System. For this purpose, the analysis model is supported by tools and models developed by Ruiz & Bucci (2019), Clune (1983), and Bucci (2016).

Isabela Ruiz

Legal institutionality and retrogression in public policies: an analysis of the Unified Social Assistance System

The thesis examines the construction of the legal-institutional arrangements of social assistance policy in Brazil, a process that culminated in a decentralized and participatory system, the Unified Social Assistance System (SUAS). Under the Law and Public Policy (DPP) approach, the research illustrates the process of the legal structuring of social assistance policy while considering its political-institutional context. The investigation centers on the following question: how capable is the legal-institutional arrangement of providing stability to a given public policy design, preventing the retrogression of services and benefits? To answer this question, the thesis examines the history of social assistance in Brazil, with an emphasis on the period of the New Republic after the 1988 Constitutional recognition of social assistance as a right. This analysis focuses on the sequence and types of norms that structured the SUAS, highlighting the role of resolutions from inter-federative and participatory bodies—such as the Tripartite Inter-Management Commission (CIT) and the National Council for Social Assistance (CNAS)—in the construction of public policy. Finally, an analytical framework for the legal study of the dismantling of public policies is suggested.

Sergio Valente

Public Policies and the Legal-Institutional View: the Case of Basic Sanitation in Brazil

This paper aims to investigate and map the characteristics and flaws of the legal-institutional arrangement of the national policy on basic sanitation, highlighting the relationship between politics and law. It also aims at the theoretical development of the subject, with the improvement of an analysis method that can be applied to any public policy. Considering the interdisciplinary nature of the subject, there is a political science approach – a historical neo-institutionalism background– aligned with a legal standpoint to make a more comprehensive analysis to extend its possibilities of use. Identifying legally qualified veto points in the various processes that comprise the sanitation policy indicates dysfunctions in the way things are organized, contributing to the increase of power imbalance between actors and the reinforcement of path dependency. These flaws have legal and political components and have helped maintain the sector model created in the 1970s, based on state-owned sanitation companies. A thorough examination of the policy suggests that this comes because of various factors, including uncertainties about service ownership, delays about indemnities at the end of contracts, waiver of bidding for state-owned companies, overlapping of roles, unrealistic investment projections, absence of a financing structure that changes the dynamics of cross-subsidies, and the lack of effectiveness of some rules, such as the obligation to edit municipal plans. These factors induce the maintenance of the status quo of low coverage of services, especially the collection and treatment of sewage, which ends up with the worst coverage rates.

Alexandra Fuchs de Araújo (State judge)

Judicial Review of Housing Public Policy

The objective of my Ph.D. thesis was to investigate the ability of the Judiciary to carry out a more efficient control of housing public policies. The Brazilian Judiciary has many legal instruments to control public policies. But when the subject involves land conflicts, there is some difficulty in dealing with constitutional values. My objective was to find ways – based on the Constitution and the civil procedure code of 2015 – to weaken the authority of some Brazilian statutes concerning property protection, in its more traditional sense, to make them more compatible with constitutional values.

In my work, I had some basic assumptions. First: the Judiciary doesn’t deal well with lawsuits involving the fundamental right to housing, especially concerning expropriation and repossession. This fundamental right might be infringed upon, thus bringing consequences to the community and a city’s land distribution. Second: people removed from territory in compliance with a judgment in an expropriation or repossession suit are not formal parties – they are not owners, but they will suffer the consequences of the decision, and so will the city. Third, the Judicial Power’s ordinary solutions (based on the traditional sense of law) ignore the right to housing for the poorest and the legislation about urban territory. Fourth: norms involving expropriation and repossession must be interpreted from the point of view of the Constitutional perspective and the Civil Procedure Code of 2015. We already have legal instruments to change the traditional sense of law concerning urban land and expropriation and repossession. Judges can create an environment for negotiation and cooperation between interested parties while encouraging the government to preserve the fundamental right to housing. But it seldom happens.

Aiming to protect the fundamental right to housing of the poorest people in expropriation and repossession while maintaining democratic institutions, I created the Guide of Judicial Review of Public Policy (GJRPP) to support judges and interested parties in lawsuits related to land conflicts. The Guide is inspired by the Quadro de Problemas de Uma Política Pública (Public Policies Problems Framework, RUIZ; BUCCI, 2019) and can be used in conflict or disputes involving consequences to the right to housing of the poorest people. The main idea is to stimulate the development of housing public policies and to support judicial decisions that provoke the government to find better solutions to expropriation and repossession.

Appendix B

Neutral principles, autonomy of law, conflicting values, critical legal studies, autopoiesis, and our behavioral model of law and public policy

Bill Clune, 7/23/22

The recursive political model of policy presented in this article might seem to diminish the autonomy of law (see the graphic accompanying note 8 above). What is law supposed to be autonomous from? Several answers come to mind – from politics, executive interference, personal value judgments of judges, public opinion, society, and social change. In general, law is autonomous to the extent that it has independent internal dynamics. Here I come down in favor of what is sometimes called relative autonomy of law or semi-autonomous law. Law is part of society and social change (not autonomous), has internal dynamics (autonomous), is the law in force at any given time (autonomous), tends to reflect the status quo (not autonomous), and is full of contradictions and compromises (both autonomous and not).

The idea of neutral principles of judicial reasoning is one version of autonomous law.[29] Critical Legal Studies deconstructed and “decentered” the apparent neutrality of judicial decisions by uncovering contradictory value judgments and principles in legal reasoning. Other versions of autonomy were developed by the late Niklas Luhmann and Professor Gunther Teubner who postulated that legal rules and decisions are self-referential to other rules and decisions assuring stability and continuity. Teubner’s concept of reflexive law proposed limits on regulation.[30] Both ideas of neutrality are correct but incomplete. Legal reasoning does contain contradictory values, ideologies, and policy preferences, and these are self-referential or self-replicating to some extent. But there is freedom of movement across contrary interests which is characteristic of both law and society. Limits on regulation are not limited to a subset of problems but are characteristic of the compromises up and down the legal system.

A behavioral explanation of such flexibility is that law is both a dependent and independent variable relative to society. Society influences law and law influences society. An important implication of our model (again, see the graphic accompanying note 8 above) is that law is formed from the influence of balance of conflicting tendencies (political resistance, change agents, etc.), and the net result of these oppositional tendencies is embodied in laws and decisions at any given time or period. This is a version of a “constitutive theory of law.”[31] A constitutive theory of law recognizes that law is simultaneously a “dependent variable,” influenced by society, and an “independent variable,” having influence on society. Law is a part of society rather than an autonomous force.

Interestingly, law and economics paints a picture of constitutive law. If judges choose the “least cost avoider,” the decision most likely is contained within the palette of precedent. The least cost avoider is the contending party that is in the best position to avoid risk. The drive toward efficiency comes from society (law as a dependent variable), and the decision aims to create more social efficiency (law as a dependent variable). Law and economics research identifies slices of constitutive law that are influenced strongly by considerations of efficiency or should be.

Under the view of law as constitutive of compromise, there is no such thing as a “neutral principle” in the sense of an objectively preferable resolution of competing values. Or a legal process that can reliably generate such objectively preferable balances. The political and social formation of law generates conflicting principles and compromises. Judicial decisions that contain contradictions may be “incoherent,” in a phrase from CLS. But law does not disintegrate, disappear, or lose binding force just because it is logically incoherent. Conflict of values is intrinsic to law. Durable sets of enacted rule compromises we call institutions.

What judges are doing, therefore, is locating a decision at some point along a continuum of competing values and policy preferences available in the repertory of existing law. Sometimes judges step outside precedents by invoking equitable principles which are sensitive to the configuration of facts before them. Llewellyn was a legal realist who understood much of this about judicial behavior.

A valid criticism of an equal balance of contradictory principles is that it results in a preference for the status quo which is one reason why lawyers and judges often operate as a conservative influence. The status quo necessarily embodies established hierarchies such as the sanctity of property and old traditions. Property usually is given strong weight, and those affected by decisions of property owners may not even have standing.[32] Adding to the imbalance, legislators and judges often decide in favor of conservative social groups because of the abundant financial resources available to propertied interests in litigation and lobbying (as when corporate law firms overwhelm regulatory agencies with torrents of legal process). Nevertheless, decision makers may move law left or right or to the middle. Law is not compelled to be in the middle of the road any more than social change is forbidden in society. Leftward precedents are in the palette of prior decisions. Social change and rebalancing of interests are possible, as with Brown v. Board and procreative privacy.

As for whether compromise is “selling out,” any behavioral (positive) theory of law must study the actual balance of competing values, the compromises in place. Criticism of compromise is normative. Distance from the ideal corresponds to the aspirational goals of some pollical actors (and authors). Critics are saying what the law should be — the counter factual rather than the factual. Criticism only makes sense as it relates to the status quo, that is, the empirically observed state of compromise. In a causal diagram, advocates for change must be represented as actors in the system usually striving for a better compromise in their direction.

To conclude, is law “autonomous”? Yes and no and yes. Yes, because it has internal dynamics of formation and impact. Yes, because it represents the current binding resolution of contending forces that have the force of law. It is “the law.” No, because it is embedded in society, shaped and being shaped by the social world of which it is a part. No, because it is not created through a value-free process divorced from society. Legal autonomy is useful analytically for exploring how law is both dependent and independent of society. But a quest for some ideal degree of autonomy is confusing. Our LPP model truer to the facts and simpler to understand.

[1] Voss-Bascom Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Wisconsin-Madison. This article is intended as the first chapter in a subsequent book edited by Professor Maria Paula Dallari Bucci. Professor Bucci made comments reflected in the text, and the article was influenced by previous collaborative publications as reflected in note 3. The article also reflects two classes I taught remotely for Professor Bucci’s students, with Professor Bucci doing a substantial part of both classes. Professor Bucci and her students independently discovered my earlier works discussed in this article, translated them into Portuguese, and contacted me about a collaboration. See note 8 infra. From the onset she understood how my work could be generalized to LPP. A point she emphasized is that LPP can be centered on law and law-in-action.

[2] Professor Maria Paula Dallari Bucci, University of São Paulo (USP) Law School, http://pos-graduacao.direito.usp.br/orientadores/maria-paula-dallari-bucci/ https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Maria-Paula-Bucci

[3] Professor Bucci and I wrote companion blogs on the New Legal Realism website. https://newlegalrealism.org/2022/03/31/clunemarch22/ https://newlegalrealism.org/2022/04/01/bucci-clune-a-south-north-nlr-dialogue-2-bucci/ Both were edited and reprinted in SSRN. Clune, Progressivism in the Active Free Enterprise State: Fluidity, Fragmentation, and Stability: A Case Study in Law and Public Policy https://ssrn.com/abstract=4095403; Bucci, Law and Public Policy in Brazil and the United States: A North-South Dialogue, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4095414

[4] https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4154531

[5] On public goods, see June Sekara, Public Goods in Everyday Life https://www.bu.edu/eci/files/2019/10/PublicGoods.pdf quoting, “The history of civilization is a history of public goods… The more complex the civilization the greater the number of public goods that needed to be provided.

Ours is far and away the most complex civilization humanity has ever developed. So its need for public goods – and goods with public goods aspects, such as education and health – is extraordinarily large. The institutions that have historically provided public goods are states. But it is unclear whether today’s states can – or will be allowed to – provide the goods we now demand.” -Martin Wolf, Financial Times.

[6] Political resistance to higher taxes is a common limitation on spending for public goods at all levels of government. The practical question is the size of the public benefit relative to the taxes, and how much taxation will be tolerated, a question which is settled one initiative at a time.

[7] Ernst, D.R. (2000). Willard Hurst and the Administrative State: From Williams to Wisconsin, 18 Law & Hist. Rev. 136 (2000), 22-23. Hurst described legal history as “policy in the dimension of time” in his book on Law and Society, a study of the development of workers’ compensation over time, which doubled as a legal process book because of its study of administrative agencies.

[8] Professor Bucci and her students became interested in my earlier work on these topics. Clune, W.H. Legal Disintegration and a Theory of the State,” chapter in Critical Legal Theory: A German-American Debate (Nomos, 1989) https://www.elgaronline.com/view/edcoll/9781788117760/9781788117760.00012.xml “Clune, W.H. A Political Model of Implementation and Implications of the Model for Public Policy, Research, and the Changing Roles of Law and Lawyers, 69 (1) Iowa Law Review 47 (1983). A third article has been translated and was the subject of another class with Professor Bucci and her students. Clune, W. H. (1992). Law and public policy: Map of an area. Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Journal, 2(1), 1-39. See also Clune, W.H. “A Political Method of Evaluating the Education for All Handicapped Children Act and the Several Gaps of Gap Analysis,” (with Mark Van Pelt), 48 Law & Contemp. Prob. 7 (1985).

[9] On implications of this model for theories about the autonomy of law (neutral principles, autopoiesis, etc.), see Appendix B.

[10] Fuhrman, Susan. 2001. From the Capitol to the Classroom: Standards-Based Reform in the States. Chicago: National Society for the Study of Education. See the summary: https://newlearningonline.com/literacies/chapter-16/fuhrman-on-the-origins-of-the-standards-movement

See also Clune, W.H. (2001) Chapter II: Toward a Theory of Standards-based Reform: The Case of Nine NSF Statewide Systemic Initiatives https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810110300802

[11] See Tribe, Laurence H., Politicians in Robes, vol. LXIX, no. 4, The New York Review of Books (March 10, 2022). In a review of a book by retired liberal Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, Professor Tribe is skeptical about Breyer’s embrace of the view that jurisprudential differences on the Court (e.g., originalism v. evolution in light of changing circumstances) explain decisions which therefore are largely free of ideological and political bias, as opposed to the idea that doctrines serve as proxies for ideological views. “Through most of the Court’s history, we have seen it rule in ways that undermine [democratic] values. The only significant exception was the remarkable period from the mid-1950s to the late 1970s. Today the Court appears once again set on an antidemocratic trajectory, one more deeply entrenched and less amenable to a change in course.”

A new threat to democracy from SCOTUS is the independent state legislature doctrine. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/06/30/supreme-court-federal-elections-state-legislatures/?utm_source=alert&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=wp_news_alert_revere&location=alert

Rick Hasen: “Pause on that for a moment: the theory in its extreme is that the state constitution as interpreted by the state supreme court is not a limit on legislative power. This extreme position would essentially neuter the development of any laws protecting voters more broadly than the federal constitution based on voting rights provisions in state constitutions.”

“And this theory might not just restrain state supreme courts: it can also potentially restrain state and local agencies and governors implementing rules for running elections.”

A grave threat, remote but far from impossible, is a right-wing constitutional convention that would remake the constitution in the conservative image. https://www.businessinsider.com/constitutional-convention-conservatives-republicans-constitution-supreme-court-2022-7

[12] Millhauser, Ian (2021). The Agenda, How A Conservative Supreme Court Is Reshaping America (Columbia Global Reports).

See also West Virginia v. EPA https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2022/06/30/supreme-court-epa-climate-change/ (discretion of administrative agencies requires clear Congressional authorization which is dysfunctional in a time of Congressional gridlock).

See also Davenport C. (June 19, 1922), The Republican Drive to Tilt Courts Against Climate Action Reaches a Crucial Moment. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/19/climate/supreme-court-climate-epa.html?referringSource=articleShare

The article describes a long-standing conservative/ Federalist Society drive aimed at limiting the discretion of administrative agencies to act within the scope of powers granted by Congress.

[13] Together with colleagues I did research on what became successful state court litigation seeking both equity and adequacy in school finance based on educational clauses in state constitutions. See Clune, William (1994) The Shift from Equity to Adequacy in School Finance https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904894008004002 Both threads had substantial impact on state funding systems in the U.S. Adequacy was reviewed for Ontario, Canada. Using the Evidence-Based Adequacy Model across Educational Contexts: Calibrating for Technical, Policy,and Leadership Influences. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1205552.pdf (“Odden and Picus (2014) drew on William Clune’s (1994) articulation of adequacy “as being adequate for some purpose, typically student achievement” (p. 377), to describe school finance adequacy as “providing a level of resources to schools that will enable… all, or almost all students … to meet their state’s performance standards in the longer term”). For a thorough survey of equity and adequacy across multiple states, see The Adequacy And Fairness Of State School Finance Systems (Rutgers University, Albert Shanker Institute, December 2021) https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED616520.pdf

States also can serve as buffers protecting democracy. See Jessica Bulman-Pozen & Miriam Seifter (2021). The Democracy Principle in State Constitutions Michigan Law Review Jessica Bulman-Pozen & Miriam Seifter (2021).

https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol119/iss5/2

https://doi.org/10.36644/mlr.119.5.democracy

This article explains that state constitutions have commitments to popular sovereignty, suffrage, election of executive officials and judges, restraints on partisan gerrymandering, public purpose limitations, initiatives, and referenda. I would add that state protections for democracy are a silver lining in the U.S. Supreme Court’s retreat from democracy and progressive legislation under the banner of federalism. Democracy can survive at least in states with progressive majorities, lack of conservative partisan gerrymandering, and progressive or non-reactionary governors and state judges. Progressivism can survive in blue cities, blue states, and some purple states. But this piecemeal approach is not sufficient to deal with most of the nationwide problems which require action by a national government.

[14] See Thomas Friedman on the partnership model built in Lancaster, PA, where a core planning group from government, the university, health care, and businesses, developed the “Hourglass” plan to revive a fading city. Thomas Friedman, Where American Politics Can Still Work: From the Bottom Up, New York Times (2018). https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/03/opinion/community-revitalization-lancaster.html Cities often have human, social, and financial capital (resources) not available elsewhere.

On active university/ community projects see https://www.epicn.org/

[15] Rebecca Hasdell (July, 1920). What We Know About Universal basic Income A Cross-Synthesis of Reviews https://basicincome.stanford.edu/uploads/Umbrella%20Review%20BI_final.pdf See also Dylan Mathews (2017) The 2 most popular critiques of basic income are both wrong https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/7/20/15821560/basic-income-critiques-cost-work-negative-income-tax and see An Evaluation of THRIVE East of the River: Findings from a Guaranteed Income Pilot during the COVID-19 Pandemic (Urban Institute, 2022) https://www.urban.org/research/publication/evaluation-thrive-east-river-findings-guaranteed-income-pilot-during-covid-19 (the THRIVE program in Washington D.C. designed to provide relief during COVID and one of the guaranteed income experiments in cities and local communities across the country. Many of the programs are inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who advocated for direct cash support to combat poverty. The Urban Institute issued a report on the results of an evaluation of THRIVE and found positive results on reduction of hunger, mental health, and non-depletion of savings. Recipients spent the payments largely on housing (e.g., rent), food, transportation, internet, and repayment of debt. Many were able to catch up on rental payments. In comparison to the cash payments, unemployment insurance is bureaucratic, complex, and inefficient, especially for the poor and minorities. Many recipients of THRIVE did not even apply for UI).

[16] Child care programs like paid parental leave are common throughout western democracies including Britain post Thatcher but have long been stymied in the United States by racial divisions and politics. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/21/opinion/racism-paid-leave-child-care.html

[17] Michael Kimmelman (June 14, 2022). How Houston Moved 25,000 People From the Streets Into Homes of Their Own

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/14/headway/houston-homeless-people.html (movement of people from homeless encampments to one room apartments rather than multi bed homeless shelters).

[18] Christopher Flavelle (June, 2022) As the Great Salt Lake Dries Up, Utah Faces An ‘Environmental Nuclear Bomb’ https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/07/climate/salt-lake-city-climate-disaster.html (potential danger from toxic dust and loss of recreational industry will require difficult tradeoffs of agricultural and urban water use with the beginning of a state/ regional/ municipal public planning already facing political resistance)

[19]David Kirp, Pre-K Is Powerful if Done Right. Here’s How (May 6, 2022). Kirp distinguishes quality pre-school programs that involve hands on learning and problem solving, like Boston’s and many others, from low quality models that involve custodial care and ineffective teaching methods. High quality programs have been shown in many studies to have large beneficial outcomes in later years such as attendance, avoiding arrest and suspension from school, high school graduation, and college entrance.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/06/opinion/politics/pre-k-education-children.html See also the long term study of kindergarten and preschool in Tulsa https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/early-education-pays-off-a-new-study-shows-how/2022/03 and https://earlyedgecalifornia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Universal-PreK-Programs-in-the-United-States-and-Worldwide.pdf

[20] Using Your Logic Model to Plan for Evaluation https://azprc.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/CHWtoolkit/PDFs/LOGICMOD/CHAPTER4.PDF

[21] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4350496/ “In RCTs, it is important to ensure that the intervention is specifically defined and consistently delivered.” A logic model of the intervention helps specify which features of the process are deemed essential to predicted positive outcomes. A user friendly guide to RCTs in education is here https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/pubs/evidence_based/randomized.asp

[22] As pointed out below, quantitative research designs require special training and degrees. I did one exercise in cost benefit analysis. Clune, W.H. (2002). Methodological strength and policy usefulness of cost-effectiveness research, in Levin, H. & McEwan, P., Cost-Effectiveness and Educational Policy. 2002 Yearbook of the American Education Finance Association, Eye on Education, Larchmont, N.Y.

[23] Designing and Conducting Case Studies https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=60

[24] Zaidah Zainal (2007). Jurnal Kemanusiaan pp. 1-2 Case study as a research method. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/11784113.pdf

[25] “Clune, W.H. A Political Model of Implementation and Implications of the Model for Public Policy, Research, and the Changing Roles of Law and Lawyers, 69 (1) Iowa Law Review 47 (1983)

[26] Meena Bose and Andrew Rudalevige, eds. (2020). Executive Policymaking The Role of the OMB in the Presidency (Brookings Institution Press), see summary https://www.brookings.edu/book/executive-policymaking/

[27] See Clune, note 3 supra and https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4095403

[28] As for courses in U.S. law schools, courses covering the federal regulatory programs taken by many students in the second and third years can be well taught from a policy perspective. Income tax, antitrust, securities regulation, labor law, environmental law, bankruptcy, and other courses were enacted with the purpose of achieving certain effects and are built on various assumptions, for example, about sound policy and fairness. Published research on the policy issues is plentiful. Criminal justice in the first year as taught at Wisconsin Law School is a policy-oriented course oriented to the exercise, control, and impacts of discretionary decisions at every juncture of the system from investigation to sentencing and parole. Likewise, contracts law in action developed at Wisconsin emphasizes underling purposes of contract law, practicalities like remedies, and enormously prevalent relational contracts where regulation occurs between trusted partners. Property and torts can be taught in a framework of law and economics. Property can include aspects of the New Legal Realism such as obstacles facing minorities in building wealth. This law in action perspective is law-centric LPP and not the same as the research-oriented interdisciplinary approach described in this article, but such research is readily available for selective inclusion and informing of teaching. Cf. Clune, W. (2021). Legal Realism to Law in Action, Innovative Law Courses at UW-Madison, Quid Pro Books.

[29]https://www.encyclopedia.com/politics/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/neutral-principles Wechsler maintained that constitutional cases should be based on “neutral principles” broader than the case at hand. Wechsler personally favored the decision in Brown but was unable to identify a neutral supporting principle. He argued that freedom of association supported both sides in segregated schools. My memory of this debate is fading, but one wonders why equal opportunity, or unequal stigma, or race neutral government policies were not sufficiently neutral and better attuned to both to the case and sociological context. When different neutral principles lead to different results the choice of principles is not neutral, but some may be better founded in justice as well as political and social realities. In that regard, neutral principles were partly a reaction to legal realism which held that judges were influenced social trends, seemingly equating law with politics. A later group of scholars in the “legal process” school found independence from politics in “reasoned elaboration.” As a Legal Process member himself, Wechsler saw reasoned elaboration as a safeguard against the Court becoming a “naked power organ.” … Opponents of the Legal Process scholars doubted whether reason alone could achieve neutrality or was a sufficient basis for deciding cases. See https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2448731

[30] https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2448731

[30] See Rowgoski, RolF,. Autopoiesis and Law (2015),

file:///Users/BillClune/Downloads/AutopoiesisinLawC86058_9780080970868.pdf

My memory of this area is dated and may overlook more recent developments. Luhmann’s theory of autopoiesis holds that the autonomy of law is maintained through internal processes of self-reference. “Only the law can change the law.” Politics has an impact, but the legal system reproduces itself only through legal events. Professor Gunther Teubner argued that the modern legal system is characterized not only by formal and substantive rationality but also by reflexive legal rationality. Reflexive law emphasizes limits on legal regulation which confronts problems such as non-compliance, excessive legalization, or regulatory capture. Regarding reflexive law, “societies might be better off with procedural or constitutive rules rather than strict substantive regulative rules. Constitutive rules are rules that induce stakeholders in an issue to reflect on their own actions; to adopt a critical view of their own operations and management. The presumed advantages of reflexive law have been summarized by Orts: it is less costly and more flexible; it can mobilize the technical skills and resources that a central government can hardly provide; and it can be tailored to suit those directly involved. This adaptive capacity allows for direct links between making the decisions and living with the consequences, thereby fostering a greater commitment towards implementation (Orts 1995).”

Glasbergen, Peter (2005). Decentralized reflexive environmental regulation: Opportunities and risks based on an evaluation of Dutch experiments. Environmental Sciences December 2005; 2(4): 427 – 442.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/15693430500405997

From my perspective, the limits of regulation are adjusted by compromises up and down the regulatory system from enactment through implementation responsive to the foreseen and actual impacts of law. Law is two-way rather than one-way, but legal rules are essential as the foundation of compromise. The limits of regulation specified by Teubner as postulates of reflexive law are valid but are a subset of the compromises pervading the legal system.

While at European University Institute at the invitation of Professor Gunther Teubner I wrote an article on autopoiesis and implementation. The article argued that the interface between regulation and organizations becomes a negotiated autopoietic space self-organized around compromises. The tacit agreement worked out during implementation is the law-in-action until changed by further negotiation. The regulator and regulated are at least temporarily satisfied. An example might be an OSHA inspector who, going by the book, orders a factory to move barriers along the assembly line further back. The factory says that would be too expensive, and they settle on an intermediate distance. Once again, the law in action is both autonomous (a stable agreement) and not autonomous (the produce of negotiation and compromise and subject to change). Clune, W.H. (1992). Implementation as Autopoietic Interaction of Autopoietic Organizations, in G. Teubner & Alberto Febbrajo (eds.). State, Law, and Economy as Autopoietic Systems (Milan: A Giuffre, 1992).

[31] A constitutive theory of law seeks to avoid the view that law is either autonomous from or completely determined by society in favor of an interactive relationship between law and society in which each has influence on but is not reducible to the other. Michael Osborne, “Explorations in Law and Society: Toward a Constitutive Theory of Law” (1995) 4 Dal J Leg Stud 293.

[32] See the project of Alexandra Fuchs de Araújo (State judge), Judicial Review of Housing Public Policy in Appendix A above.